The Eleventh Hour

/I had been at the helm 14 hours already. Too long. I was mentally worn out. We had gone out to sea. It was our final run up to NYC. We were exhausted. It was 2am. A Saturday morning. We were emerging from the NJ Intracoastal Waterway--in inland route through connected rivers, bays and inlets--into a place called the Manasquan Inlet, about 25 miles south of New York Harbor. The plan was now to head back out into the Atlantic Ocean. I would get the sails set and then turn the helm over to the Orton ladies until 6am, at which point I would wake up and sail us into NYC.

We were pounding into the on-coming seas, running both engines, our sails aloft but luffed. We wanted to motor out far enough out so we could turn north toward NYC and sail with enough distance between us and the coast so not be pushed back onto the rocks. The rigging rattled in that disconcerting way that makes you think the whole thing is going to come apart, and the slack sails slapped and thrashed with the slippery sound of dacron. The deck pitched like a bronco. Then something broke loose, silently. I didn't know it until I saw it. The safety bar that attaches our dinghy onto the stern davit broke open. The dinghy was dragging askew in the ocean behind us, dangling from a chain that was clipped to the lifting line. The contents of the dinghy were spilling out into the night sea: the oars, the bench seat. We watched it drift away, helpless to get at it without risking much more. I'd had enough. I made the decision. "We're turning back. We'll regroup and then figure out what to do." Nobody wanted to go back, but we all knew it was the smart thing to do. We turned down wind and headed straight back for the rocky entrance to the Manasquan Inlet.

We crossed under the train lift bridge, picked a spot in the tight inlet, and dropped anchor. Once we settled in, I realized we were still in the channel, like sticking your leg out into the aisle. So we pulled anchor and tried to tuck ourselves further out of the channel. I bore down on the port engine to set the anchor. I heard a quick thud and the engine stopped hard. Great. One more thing to deal with. We set the anchor using the starboard engine. Then I sat down on the port stern and stared off into the blackness of the night. I was spent. We'd pushed too hard. We wanted to get home, but we should have stopped. We should have rested. As I sat there, useless, Emily went to work sorting out the dinghy chain, lines, attachments, etc. Then Karina called up from inside, "The bilge is really full." "Turn on the pump," was all I could manage. "It's coming up really fast." "Okay. I'll come take a look." It was not good. The floor boards on the port side were floating. Water was starting to spill over the door thresholds into the cabins. "I can hear gushing water," Karina continued. I listened. It was coming from the engine compartment. I rushed up on deck, opened the engine compartment--right where I had been sitting moments before--and saw water rising up like a spring from the underside of the boat. "Start bailing!" I barked, and Alison jumped into the compartment with a bucket. "The rest of you, we're pulling anchor. I want docking lines and fenders on the port side." The boat was now listing deeply on the port side. A fuel dock stood 100 yards behind us. "We going to lash the boat to those pylons so we don't sink." I got the starboard engine running and edged forward to take tension off the anchor chain. Emily, Karina and Jane got everything in place quickly and precisely. We moved over the anchor and pulled it up. We spun 270 degrees counterclockwise to get the right approach angle since we only had one engine. "Okay everyone, we've got one chance to get this. As soon as we touch, I want you off the boat and on the dock. Jane, you go and find help. Anyone. Tell them 'our boat is sinking and we need help.'" The dock was wide open. Plenty of room for our boat. Fluorescent flood lights lit up the whole length, an easy target. But then I saw something in the shadows. A small boat was tucked along one end of the dock. It was a beautiful Ralph Lauren type wooden motor boat, standing maybe 4-5 feet out of the water. Just low enough that I was hidden by the shadow of the flood lights. "Does everyone see that boat? We've now got no room for error. We have to hit this spot on." Fortunately, we did. Karina and Emily were off in one touch, lashing the boat to the dock. I came right behind them, letting the engine still run. Jane went running down the dock, barefoot, looking for any signs of life in the marina at 2:30am. We tied a bowline knot around two pylons for the stern and another bowline knot around two pylons for the bow. The boat was secure for now. Alison was still bailing. Jane was out there in the darkness.

"Okay, everyone inside. We need to bail," I announced. (I was taught the only time you make announcements in a marriage is when there is danger. e.g. 'Get out! The house is on fire.' The rest of the time you make proposals. This was a time for announcemenets.) Karina took over in the engine compartment and Alison took a break. It was relentless work. The water was still rising, so we worked fast to move books and clothes out of the water, all while trying to keep pace with the inflow. I knew we couldn't keep this up for long. We were exhausted before this started. Now all we had going for us was adrenaline. I went to the engine compartment. The water was definitely coming from the sail drive, the part that attaches the propeller outside the boat to the engine inside the boat. The rope between the snagged prop and the deck cleat, where it was originally tied, was tight as a wire. I didn't know if that was related to the problem, but I figured it was a good place to start. I went below and found my knife. I came above deck and cut the line. Snap! "Woah!" Karina yelled from inside the engine compartment. "What?" I asked. "The engine just moved like two inches." "Okay, that's good," I replied. "The water seems to be coming in slower," she observed. "Good. Keep bailing. I'm going to call for help."

It took me 10 minutes or so, but I finally reached the local Sea Tow in Manasquan. (Sea Tow = AAA on the water.) Scott took the call. "I'll be there in 20 minutes." I sent Emily to the road to meet him and guide him to our boat. Jane arrived with a bleary but willing sailor, probably one of the only people living on their boat in the marina. It was just that kind of a place. The poor guy was white haired and hungover. He asked what was going on. I thanked him and recommended he go back to bed. He disappeared back into the night. Jane was back with us.

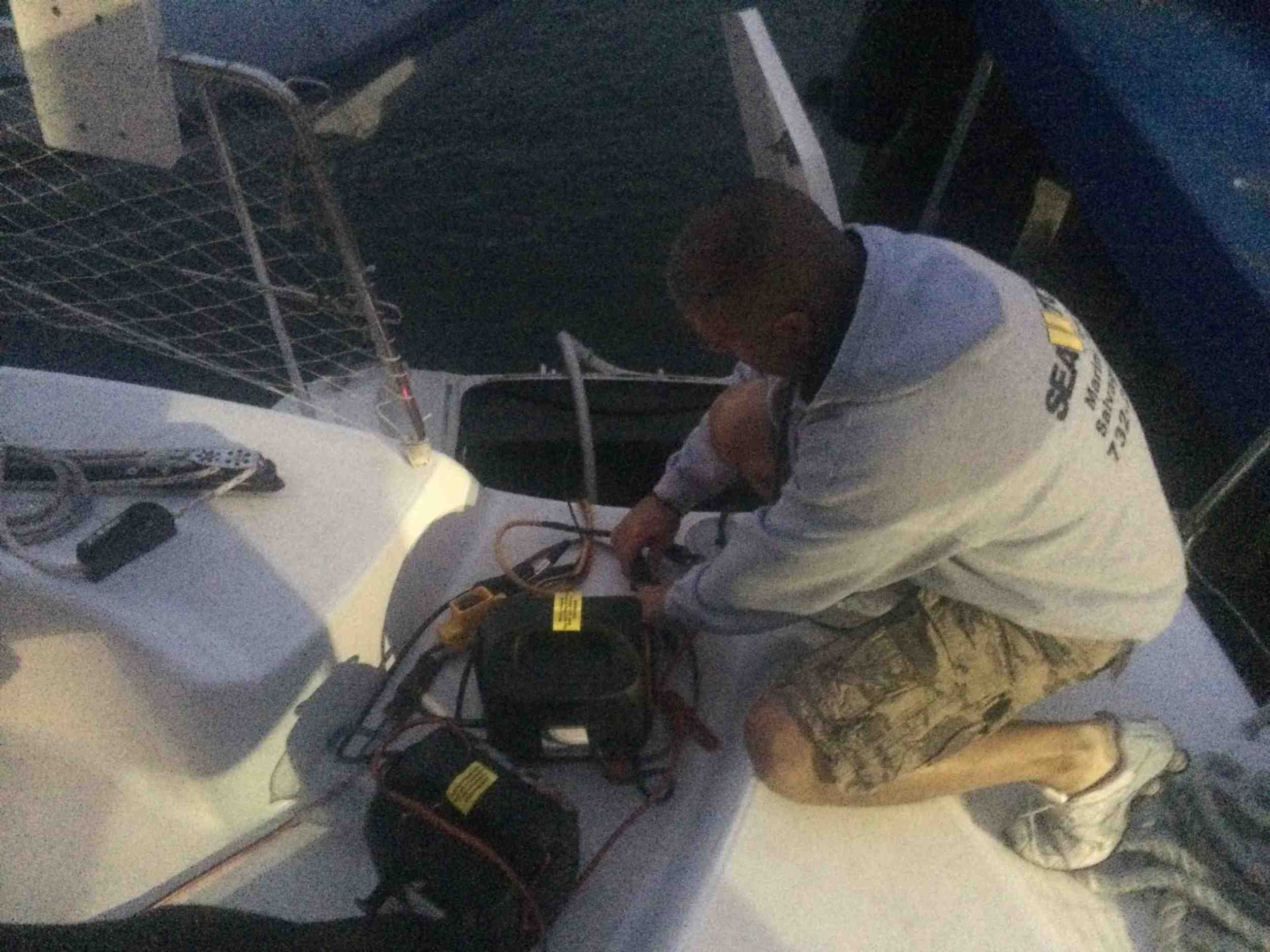

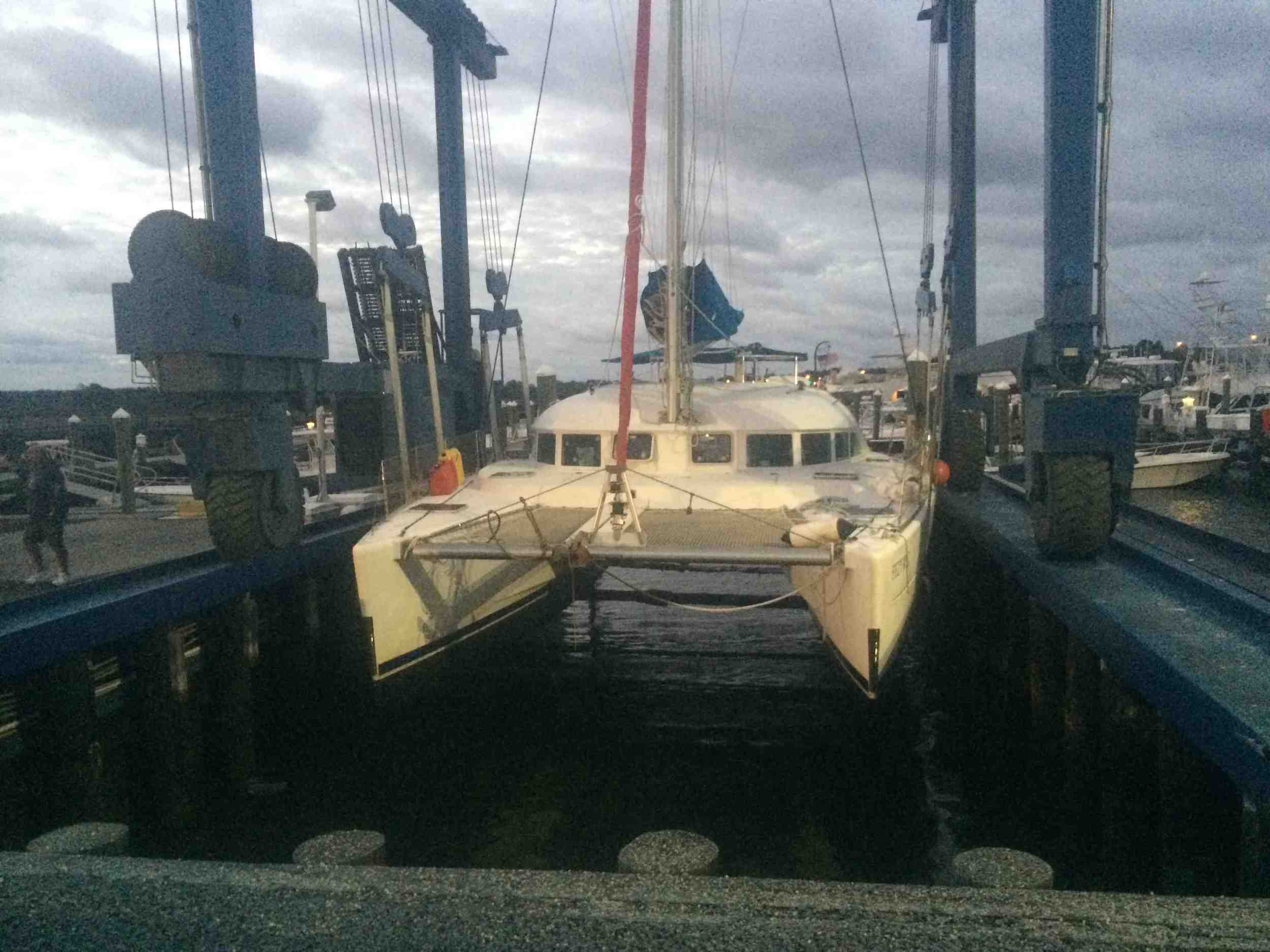

Scott arrived with high power pumps. We wired them up and shoved them down into the lowest point of our engine compartment. Immediately water was pulled out faster than it was pouring in. We stuffed sliced foam floaties around the edges of the leak. Scott contacted the marina next door. It was 4am. They had a lift big enough to haul out our boat. Their crew came en masse and got everything moving: a boat out of the lift, put it on blocks, repositioning the lift for us. Then came instructions for me: "You have to sail your boat around to that alley and come straight in and then stop before you hit the concrete wall, but don't come in too fast." Great. Just stop your 20 ton boat on a dime and you'll be fine.

The tide was slack, but was picking up. The wind was blowing out of the east and building, pinning the boat against the dock. I had one engine: starboard. That spins the boat counter clockwise. The exact wrong direction I needed to go. Emily, Scott and the Karina grabbed fenders and moved them between the boat and hard objects as I tried every trick and angle to get the boat off the dock. But in the end I couldn't get enough momentum to have control of the boat's direction. Finally, I decided to go backward.

As the boat moved down past the end of the dock, the bow began to swing around. The only problem was we were surrounded by large, beautiful, expensive fishing trawlers with long bow sprits that stuck out 5-6 feet off the front of each boat. As the boat pivoted counterclockwise, the Fender Crew moved fast to make sure no additional damage was inflicted. Free of the dock, we picked up momentum in reverse and move toward the lift alley. Imagine: a movie car chase. The car is speeding along in reverse, hits the brakes, swings around 180 and then peals off in the original direction, but now facing forward. That's what we did, but at 4 mph. Not nearly as impressive to watch, but still nerve wracking. I turned the corner into the lift alley. The guys on land were radioing instructions to Mike on the boat with me. We edged the boat a bit this way, a bit that way. Fezywig is 21 feet wide. The lift pit is 23 feet wide. Good thing I had all that practice going through narrow bridge openings in the St. Martin lagoon. We hit the center line right on. That's when the guys started shouting "slow down! slow down!". This was the 'stop on a dime' part. I throttled the boat in reverse, trying not to pivot the boat off it's line. The slings slipped under the hull and snugged safely between the rudder and keel fin on both sides. "Okay, you can kill the engine now." I finally let my body exhale.

Ten minutes later the boat was out of the water, the dinghy line dangling off port prop. The sail drive seal tear was now easy to see. This was the breach. So simple. So small. But so important. The sun was rising over the Atlantic Ocean. We'd survived the night.

Scott offered to take us to a breakfast diner to rest until rental car offices opened up. He ferried us over in two trips, then disappeared. We were grateful for him that morning. I told the kids to order whatever they wanted. And I whispered to our waitress we'd just been through a bit of a boating accident, and to please forgive us if we were a little distracted. The kids promptly began to fall asleep in our double booth. Food arrived. They ate, then fell asleep again. The diner started to fill up. "We're waiting for the car shops to open up. Can we just sit here for a while?" I asked. They were reluctant at first. This was a busy Saturday morning at a breakfast diner. But then they said, "We'll let you know if there's a line." We waited. Made more calls. No one had a car big enough for our family. I made more calls. The kids slept. The waitress came back, "You all stay put as long as you need. We'll let you know if there's a line." Emily had told them a bit more about our morning. Finally, Enterprise had a car. It was expensive, but it was right. A large, black, Ford Escapade; something Beyonce would be driven around in. They said they'd be there in 45 minutes to pick us up. We went outside to wait in the park. As we left we said thank you and goodbye to the wait staff. Outside was a line of customers waiting for a table. Those waitresses made us cry.

The Enterprise guy was here in 15 minutes. They gave us keys to our comfortable, new car and we were on our way. We went back to the boat, got some clothes and toothbrushes and drove off. We came home to a parking space right outside our apartment, a fridge full of food, a front door covered in hearts and notes from friends near and far, and our comfortable, familiar beds into which we promptly fell.

Honestly, that night was one of those moments that makes you a little gun-shy, a little afraid to get back up on the horse. I'm am terrible at writing about stuff that still feels tender. And this one has felt tender. I like to know that things are going to work out before sharing moments of vulnerability. But today I have gathered my courage about me. Work has been underway for the past two weeks to repair our port sail drive. Our boat is back in the lift, this time ready to be relaunched. Tomorrow we will go to the marina, put Fezywig back in the water and see if she floats. If she does, the plan is to sail her up the Jersey coast, into New York Harbor, up the Hudson River and to our neighborhood marina in Upper Manhattan.

Do I worry I'm jinxing myself in saying this? Of course. Sailors are superstitious. But that's the plan. If it goes as planned, we'll be pleased. It will be a hard won arrival, because part of me feels like we haven't arrived until we sail under the George Washington Bridge. That's the finish line. It's all about coming home.

Last night, I was up fretting. What if the sail drive still leaks? What if we hit bad weather? What if the dinghy comes loose, despite the changes we've made? What if? What if? What if? I was whittling myself down with worry. But this morning, as I woke up, I realized we'd already crossed the finish line: we're closer and stronger as a family, we've made wonderful friends, we're more grateful and more confident than we left. And that's why we went. Mission accomplished.

So maybe we will sail around Sandy Hook and see the Freedom Tower rise up over the horizon. Maybe we will sail past the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. And maybe we will pull up to Dyckman Landing and walk down the street to our apartment. But if not, I will still feel like we 'made it'.

After 2500 ocean miles, how does this journey end? We'll see. But we're grateful we made it this far. Thank you to all of you who have cheered us on and encouraged us every step (and slip) along the way. This will not be our last trip on Fezywig, but we're grateful it was our first.

“We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”